Planners and city officials, now keenly aware of the relationship between education and neighborhood economic development, should create new programs to harness school quality toward the equitable revitalization of neighborhoods.

Summary:

Philadelphia’s public schools are wrestling with the realities of fiscal insolvency. To close a $400 million deficit, the City recently closed 23 schools and laid off nearly 20% of the total District workforce. While the human capital repercussions will be felt for generations to come, there will also be significant neighborhood economic impacts as well. The research accompanying this project concludes emphatically that despite Philadelphia being a school quality ‘desert’, good schools still fetch a premium and great schools have the power to transform a neighborhood.

This document briefly outlines the motivation and design of an original program idea called School Improvement Districts – bounded areas whose residents vote to increase their own taxes and use the incremental increase to fund new school quality in their own neighborhoods. While the program is placed-based and thus intended to be used as a tool for neighborhood development, a principle focus on equity will ensure that vital human capital spillovers are generated as well.

Motivation:

The charter school movement in Philadelphia will continue to gain momentum and the exodus from District schools will hasten particularly in the wake of recent state legislation. The economics of this transformation will further degrade school quality by forcing the District to mitigate its fixed costs by issuing more layoffs and closing more schools. Although at face value, charters are not poor alternatives, unlike New York and Chicago which saw charter growth as a means of education innovation, in Philadelphia, their emergence is mainly in response to market forces.

Why is this a problem for neighborhoods? District schools are anchored to local neighborhoods – thus a decline in District school demand will lead to a corresponding decline in neighborhood demand. If we capitalize on this mechanism but in reverse, the question becomes – can we generate new demand for District schools in an effort to bolster demand for neighborhoods? Can this be done equitably?

Supporting research:

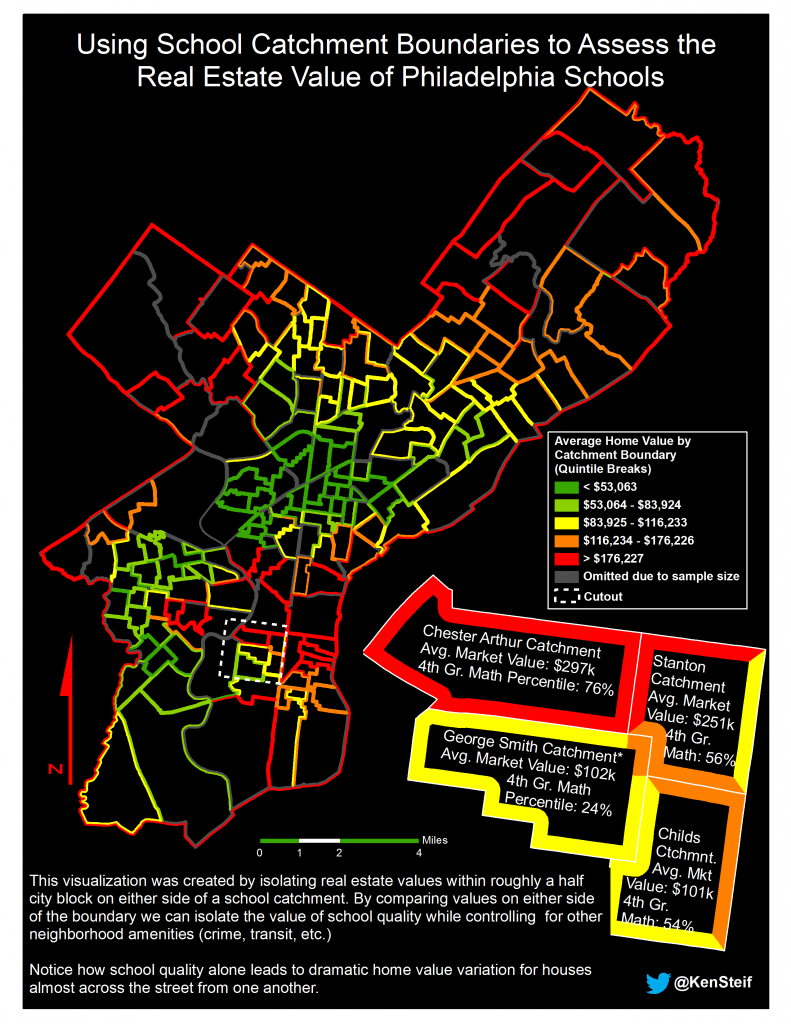

How might we identify the extent to which schools play a role in neighborhood demand? The research that accompanies this project estimates the willingness to pay for public schools by Philadelphia home buyers by way of a quasi-experiment – relating (in a regression framework) differences in test scores with differences in home prices for home sales on either immediate side of school attendance catchments. This framework can identify school related home price premiums separate from other non-school neighborhood amenities.

In Philadelphia, despite the current school crisis and a portfolio of under-performing schools, a one standard deviation increase in test scores leads to nearly a 3% increase in home prices on average. In addition to the citywide analysis, this research also tested the local economic development effects of introducing a high-quality school in a neighborhood that previously lacked school quality. Using the University-subsidized, Penn Alexander School as a case study, a decade after the school’s debut, the research estimates that the average home buyer was willing to pay a 40% (nearly $140k) home price premium to purchase a house in the school’s attendance catchment.

These results suggest that good schools can be a major driver of economic development in Philadelphia.

Policy Description:

The Improvement District mechanism is used to fund increased service provision typically in downtowns toward the benefit of local business. In 2000, Pennsylvania enacted legislation approving ‘Neighborhood Improvement Districts’ suggesting that, “…taxes many times are not sufficient to provide adequate municipal services…” and that, “municipalities should be encouraged to create, where feasible…assessment-based neighborhood improvement districts…” administered by, “…district management associations…that promote and enhance more attractive and safer…neighborhoods; economic growth; increased employment opportunities; and improved commercial, industrial, business districts and business climates.” It is believed that this legislation provides the legal framework to support School Improvement Districts.

School Improvement Districts would allow local residents to vote to increase their own taxes and put the incremental difference toward their local school. It is envisioned that these Districts would be managed by a local community development non-profit that has the experience and staff to manage such an entity. Because the new school quality will be capitalized into local home prices, this program must be accompanied by a series of equity interventions that will encourage housing affordability. The most important means to achieve equity is to draw the District boundary to encompass a mixed-income neighborhood which would give planners greater control over the supply of and demand for public services like schools. Although the Improvement District tax rate is flat, the tax is made more progressive by the fact that the tax liability is a function of home price. Thus, the tax liability of lower valued homes will be less than that on higher valued homes. Although all in-District residents will receive an equal share of the new school quality, the costs will be more equitably distributed. The second major equity component would use the promise of new school quality to win low income housing tax credits which can then be used to build affordable housing in the neighborhood before the new school drives economic and demographic neighborhood change and possible displacement.

Conclusion

Education is routinely seen as the most important mechanism for elevating children out of poverty. It is incumbent upon planners to break the negative feedback cycle where low quality schools yield ill-prepared students who grow up to earn disproportionally lower wages and are forced to live in disadvantaged neighborhoods with low-quality schools. To incentivize officials to adopt policies effective in this regard, the proposed program considers schools not only as drivers of human capital development but as engines of economic development as well. School Improvement Districts may provide one policy mechanism to bolster education outcomes while simultaneously driving the equitable revitalization of neighborhoods.

More reading:

Steif, Ken (2013). Can Improvement Districts help save Chicago Schools? Chicago Tribune: December 18, 2013

Steif, Ken (2013). Can the Success of Penn Alexander be Replicated. The Notebook.